FORMER CELTICS LEGEND DIES AT 88

The man came of age in the infancy of the NBA, but he was already a legend for his accomplishments as a collegian at the University of San Francisco.

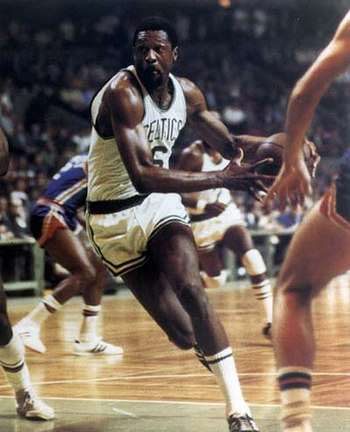

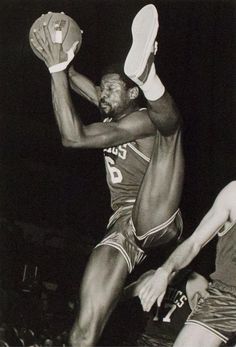

He did nothing but win, literally, being the main cog in the Boston Celtics’ glory years, an intimidating defensive presence and the main cog of THE dominant franchise of the National Basketball Association in the turbulent ’60s.

He was born and spent his childhood in Monroe, Louisiana, and he mentioned over the years that his experience in the Jim Crow South made him a hardened man, away from the game and the structure of professional basketball.

And yes, he became a legendary player in Boston, a city haunted by its own reputation with race relations while the South was being reshaped by the civil rights movement and integration.

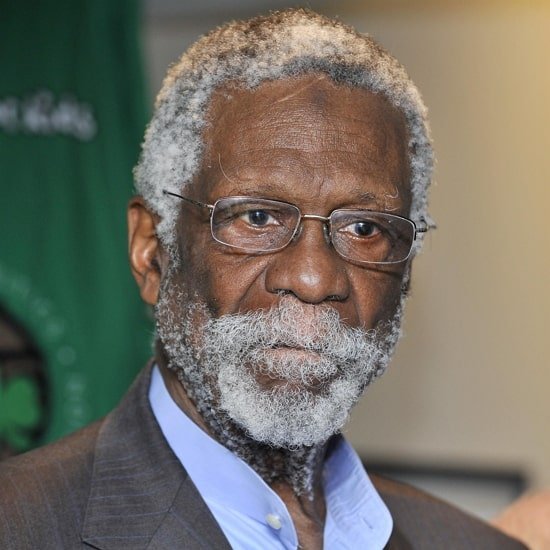

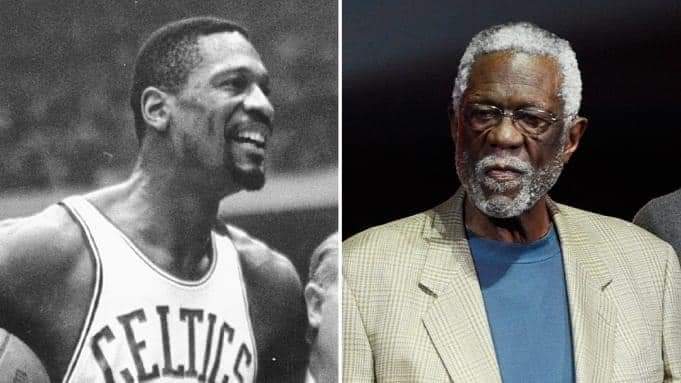

Bill Russell was one of a kind.

Russell died on Sunday in suburban Seattle, at the age of 88, but he leaves a legacy that goes a long way beyond the basketball court.

He had an infectious smile, a pronounced, high-pitched laugh, an unmistakable voice and a great appreciation for human rights, basketball excellence and racial equality.

He joined forces with the likes of the late, great Muhammad Ali, and NFL legend Jim Brown, among other prominent African-American athletes of the ’60s, when overt racism was accepted in many circles and outspoken advocates for equal rights were often criticized for simply trying to do the right thing.

Bill Russell was a man of dignity, a man of principle, and a man I’ve admired since my grade school days in Houston, Texas.

Back then, the NBA was a fledgling league in places like Syracuse, Rochester, and later, Kansas City-Omaha. (It’s a three-hour drive.)

It seems hard to believe, in this day and age, that the NBA had to market itself to the masses, but the truth of it is the biggest sports, in those days, were baseball, boxing, college football and, to some extent, horse racing.

Especially in Kentucky, as I can attest.

Basketball was popular, sure, as it was a wintertime diversion played by both boys and girls at the high school level, and John Wooden’s UCLA Bruins established college basketball as a big-time spectator sport. The NBA was limited primarily to the Northeast and the Upper Midwest in the early years, but the Philadelphia Warriors’ departure foe Golden State and the Minneapolis Lakers relocating to Los Angeles, it started to become compelling television.

And two men, above all others, made that happen.

Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain.

Chamberlain, the colorful, charismatic 7-foot-1 center, was the Warriors’ dominant player in both Philadelphia and San Francisco — they were even known as the San Francisco Warriors in those days — and he was a flashy dresser, an extrovert, a man about town who loved the spotlight.

Russell just tolerated it.

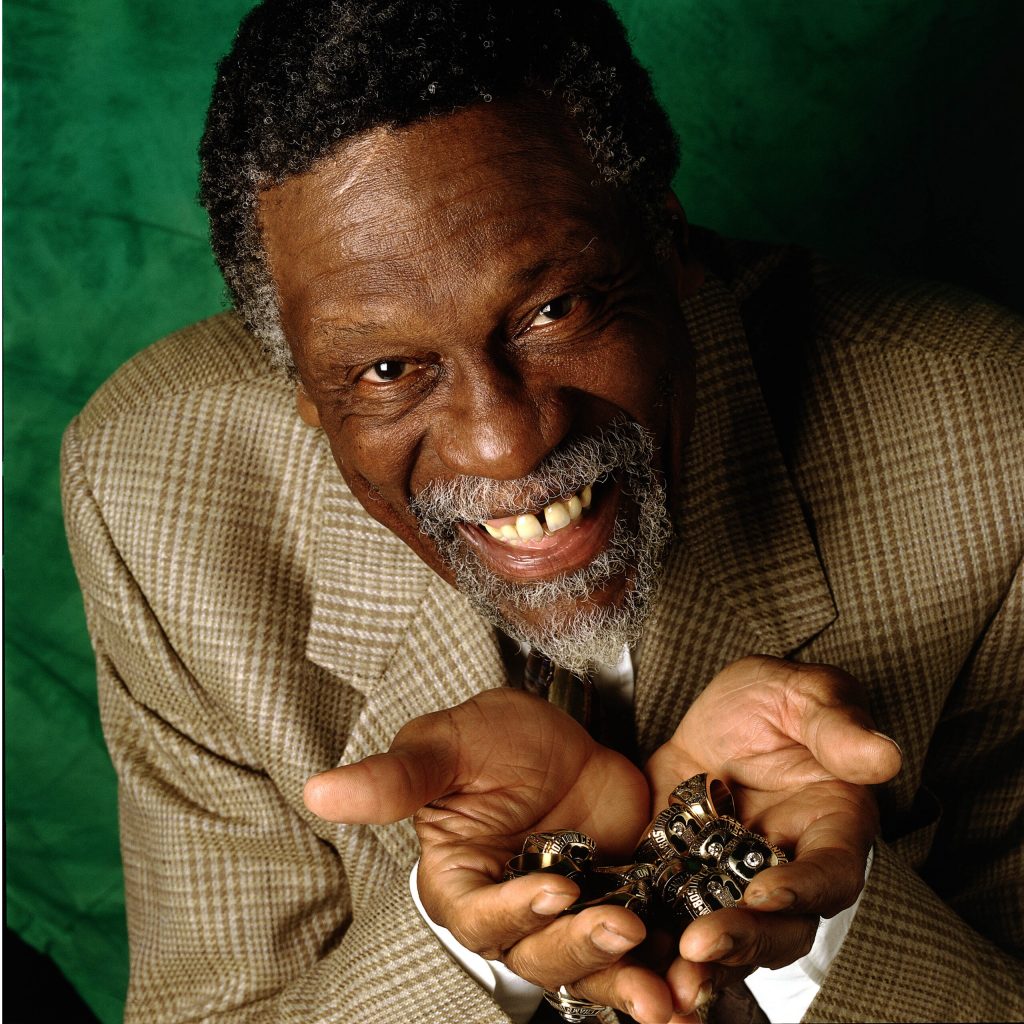

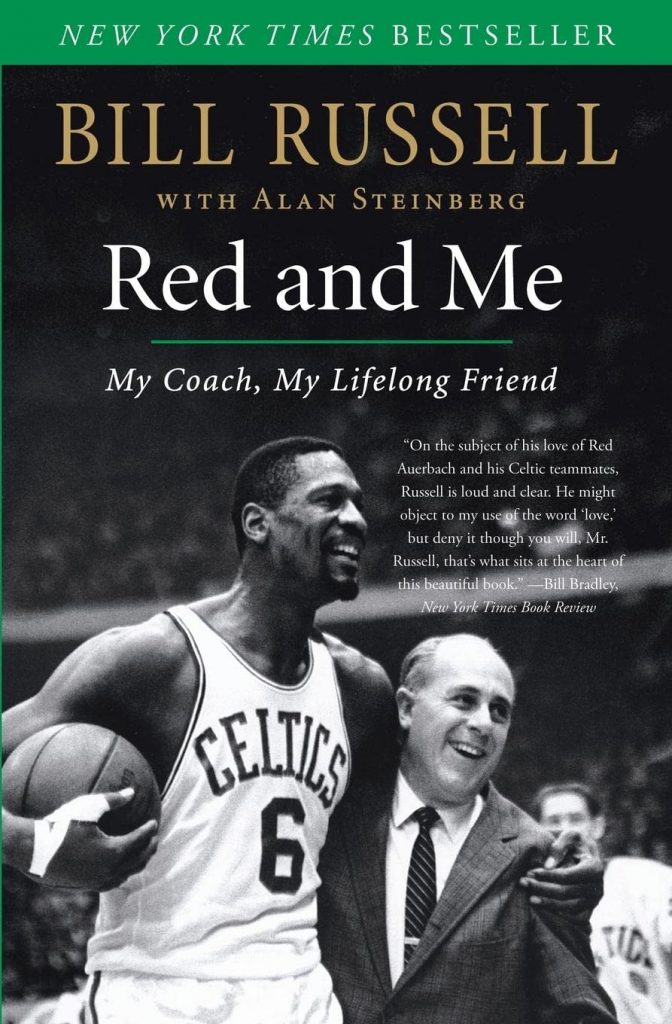

He was the ultimate teammate, and an outstanding leader. He concentrated on his defense, because that’s what Red Auerbach and the Celtics NEEDED, and he usually got the best of Chamberlain in the playoffs, winning 11 NBA championships in his 13 years in the league.

Bill Russell won his last two NBA titles as a player-coach, which doesn’t even register today in the structured world of professional sports.

Bill Russell cared about his fellow man.

Bill Russell was an American original.

Bill Russell used his stature in professional basketball in service to his fellow man, and he became one of the NBA’s elder statesmen in his golden years. He dabbled in broadcasting, penned a book or two, and worked as an NBA coach and general manager after leaving the Celtics.

He stayed true to himself.

He stayed true to the game.

And he stayed true to the Celtics, even after enduring a handful of ugly racist encounters during his days in Boston.

I met him a couple times, in media settings, and he couldn’t have been more gracious. (And very tall.) He was known to be averse to signing autographs, preferring instead to greet fans with a handshake and perhaps a brief conversation. He was an engaging man. He was bright, he was driven, and he cared about his legacy in basketball.

THE LATE RED AUERBACH.

Bill Russell became good friends with legendary journalist Frank Deford, the longtime Sports Illustrated writer who died in 2017. In 1999, Deford wrote the definitive profile on Russell, who was an awkward, gangly youth during his Louisiana childhood. He became a star in basketball and track and field in California, excelling in the high jump, and he was basketball’s shot-blocking king.

They didn’t keep that stat in those days.

We know about the rebounding titles, the championships, the activism off the court.

AT THE AGE OF 88.

But one of the things that made Russell such a great basketball player was understanding his role, and making it work. Russell won the NBA’s Most Valuable Player award five times, in 1958, 1961-63 and 1965. He averaged 15.1 points, and an amazing 22.5 rebounds per game, in his professional career.

Let me repeat that.

Bill Russell averaged more than 22 rebounds per game, in an NBA career that spanned 13 years, including 11 championships.

I know that Russell’s blocked shots stats would probably rival the sack totals of the legendary Deacon Jones, a pro football star who is actually credited with coining the term, “sack.”

A sack can erase an opponent’s offensive progess, and a blocked shot can create all sorts of opportunities when the ball is kept in play. With his 7-foot-4 wingspan, Bill Russell kept plenty of blocked shots in play, rather than sending them into the third row of the spectators.

A lot of Russell’s blocked shots wound up in the hands of John Havlicek or Frank Ramsey, and K.C. Jones was brilliant at running the Celtics’ fast break, particularly after the retirement of the legendary Bob Cousy in 1963.

But it was Russell that made the Celtics such a feared opponent. Fourteen times in his professional career, Russell and the Celtics faced a win-or-go-home scenario in the NBA playoffs. And in all 14 of those pressure points, the Celtics emerged victorious.

I remember watching some of those games, on my family’s black-and-white TV in Houston, before his retirement in 1969.

I was pretty much in awe. With his talent, with his drive, with his dedication to social causes.

Thank you, Mr. Russell.

Thank you for everything.