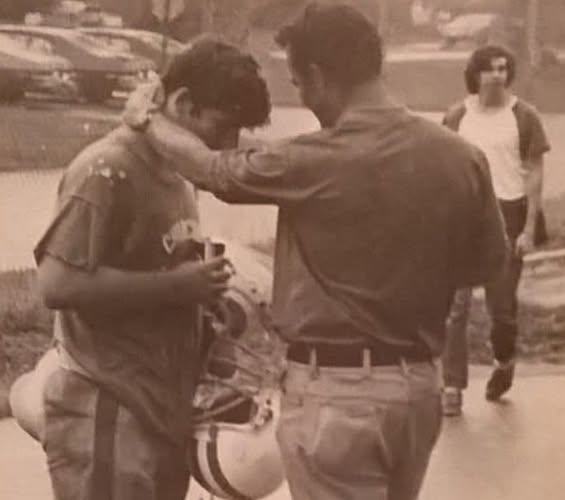

AFTER A TOUGH 13-7 LOSS

TO GAITHERSBURG IN 1973.

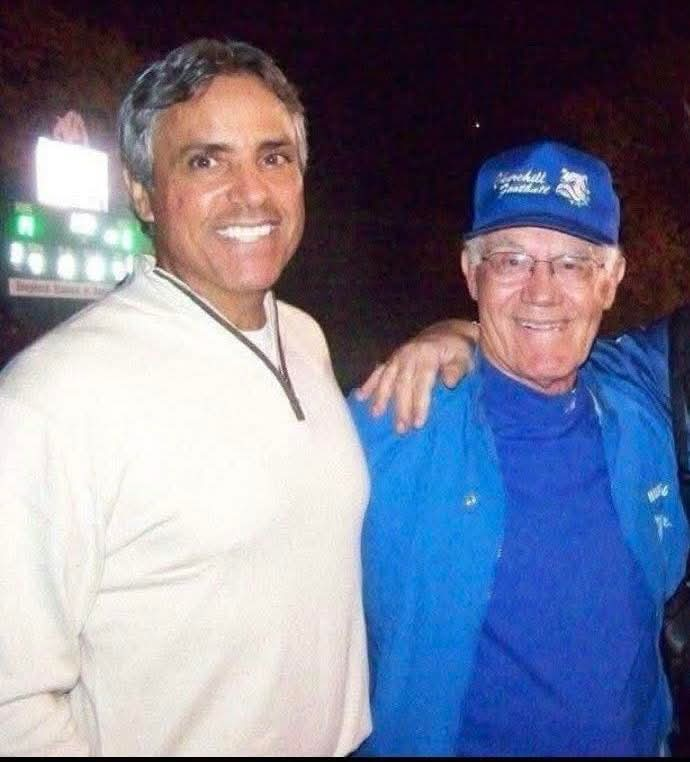

FRED SHEPHERD, A MAN DEDICATED TO OTHERS, DIES AT 86

It’s been 55 years, since my family relocated from Houston to Potomac, Maryland, and that summer, I was introduced to Fred Shepherd, the head football coach at fledgling Winston Churchill High School.

Churchill was located on the corner of Gainsborough Road and Tuckerman Lane in Suburbia, USA, in the 1970s. It definitely had a “Wonder Years” feel to it. Scores of kids, myself included, usually walked to school.

Mr. Shepherd was still a young man then, a tough, taciturn coach who always had time for others. He stood about 5 feet, 7 inches tall, and it was easy to see how he had made a name for himself as a fullback and defensive back at the University of Virginia in the ’60s.

Dude had forearms like Popeye. Definitely more of a listener than a talker. He loved football, but not nearly as much as he loved his players. His fellow coaches. He grew up in Western Pennsylvania and he understood the value of an honest buck. His Dad worked in the steel mills, and coal mines, and he was the youngest of Harry and Margaret Shepherd’s four children.

Consequently, he was known as ‘Babe’ Shepherd, a name that followed him to UVA, where he played for some Cavalier teams that usually lost more games than they won. He could have tried his lot at professional baseball, but his Dad emphasized the value of a college education, in the event of an injury or other calamity. Fred Shepherd listened to his father’s advice.

He went to work in public education, even though the NFL’s Washington Redskins, the league’s southernmost franchise at the time, had expressed interest in him, too. Mr. Shepherd served two years in the U.S. Army before accepting a job as a teacher and coach with Fairfax County Public Schools in his adopted home state of Virginia.

Then, in 1969, Mr. Shepherd became the head coach at Winston Churchill High School, which opened its doors just five years earlier. Right around the Capitol Beltway. He became synonymous with the school, and vice versa.

Fred Shepherd was the Bulldogs’ head coach for 27 seasons, and he definitely could have pursued a college career if he were so inclined. When he finally stepped down as the Churchill coach, in 1996, he remained at the school in an administrative capacity, in addition to coaching the girls’ softball team. In the first team meeting of two-a-days, he’d tell his players his office door “was always open,” and we knew that he meant it, too.

Mr. Shepherd died earlier this week, at 86, after a long bout with Alzheimer’s Disease. He set an example, for all of us, and he made a difference in so many lives. His quick smile, firm handshake and steely demeanor served him well. He understood that respect was two-way street; he demanded it, and he earned it, too.

DAN SHEPHERD, AFTER A CHURCHILL GAME.

FATHER AND GRANDFATHER.

My teammates and I loved the man. He wanted to win, sure, but he was primarily interested in character development. His summer practices could be brutal, but he emphasized player safety, responsibility and accountability, above all else.

Mr. Shepherd compiled an amazing record of 209 wins, 78 losses and two ties at Churchill. (I took part in one of those ties, in 1972, my junior year with the Bulldogs.) He won two Maryland state championships and went to the title game several other times.

Mr. Shepherd produced countless college players, and a dozen or so who actually made it to the NFL, including New England Patriots offensive lineman Brian Holloway, L.A. Rams/San Francisco 49ers quarterback Jeff Kemp, Heisman Trophy runner-up Paul Palmer and, in the twilight of his football career, longtime NFL linebacker Dhani Jones, who won a national championship at the University of Michigan in 1997.

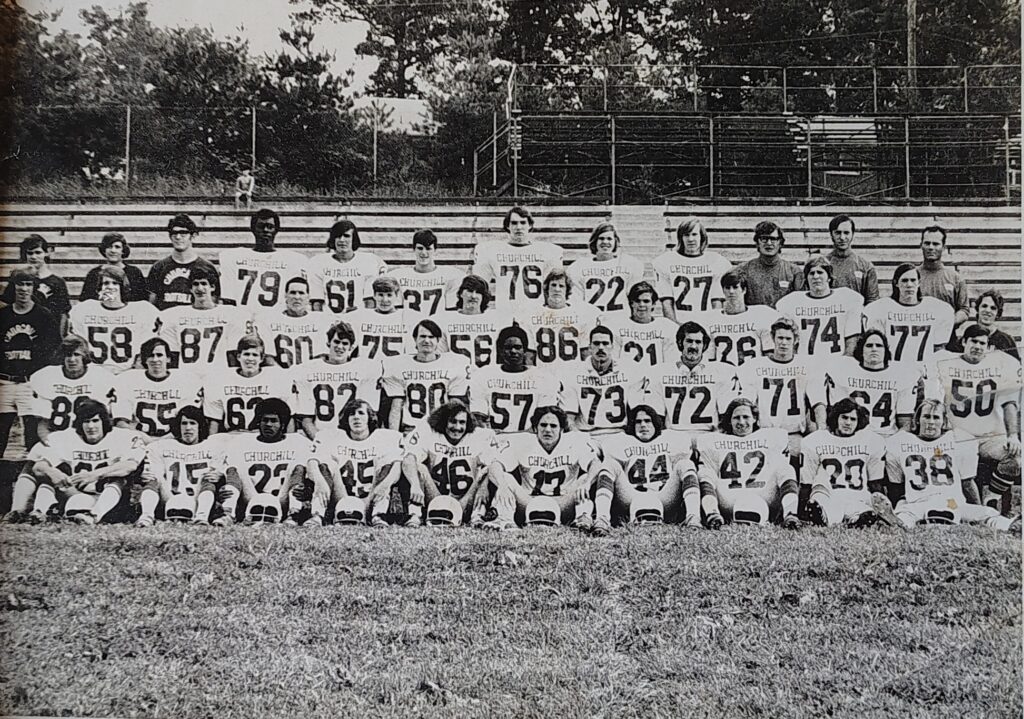

IN 1973, MY SENIOR YEAR WITH THE TEAM.

MIDDLE: PAUL DAY, LARRY JEHLE AND DAVID SAVAGE.

BOTTOM ROW: MARK HIGGINS AND MYSELF.

(One of my Churchill teammates, the late Ricky Cowen, played in the Canadian Football League after a fine college career at the University of Delaware, and Kemp’s younger brother, Jimmy Kemp, spent 11 years as a CFL quarterback, with both men following the lead of their famous father, the late Jack Kemp.)

Mr. Shepherd was thrilled that I pursued a career in sports journalism a couple years after graduating from Western Kentucky University. In 1986, I wrote a column on the aforementioned Brian Holloway, who was a starting offensive tackle for the Patriots’ first Super Bowl squad. (The less said about their performance, the better, as the Super Bowl Shufflin’ Chicago Bears crushed the Patriots, 46-10, in Super Bowl 20 inside the cavernous Louisiana Superdome.)

Mr. Shepherd had plenty of time to talk to me for that story.

Truth is, Mr. Shepherd had plenty of time for just about everyone. He was devoted to his wife, Jerrie, and their children, Dan, Terri, Sharon and Randy. He’d arrive at his cramped, tidy office, at about 6 o’clock sharp, five or six days a week. He put in long hours. And he won a lot of football games.

Most of all, he instilled a sense of pride in a lot of impressionable teenage boys. If a big, strong kid was willing to work, he didn’t have to be a great athlete. Mr. Shepherd would find a place for him. He had a warm side, to be sure, but he had to blaze his own path, to coaching excellence.

A celebration of Fred Shepherd’s life will be held at the St. John’s Methodist Church, in Aiken, South Carolina, on September 20. I’m sure scores of his Churchill Bulldogs players will be there.

We’ll always be grateful for his guidance, his discipline, and his sense of fairness. We’ll miss you, Mr. Shepherd. Godspeed.

A 209-78-2 RECORD IN 27 SEASONS

AS CHURCHILL’s FOOTBALL COACH.