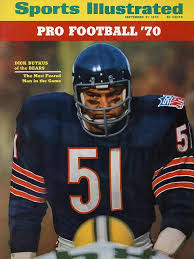

BUTKUS EMBRACED THE ‘TOUGH GUY’ IMAGE, BUT AWAY FROM THE GAME, HE SHOWED ANOTHER SIDE

He was, of course, larger than life, the original Monster of the Midway, the baddest man on the planet before Mike Tyson was even born.

And he made no apologies about it.

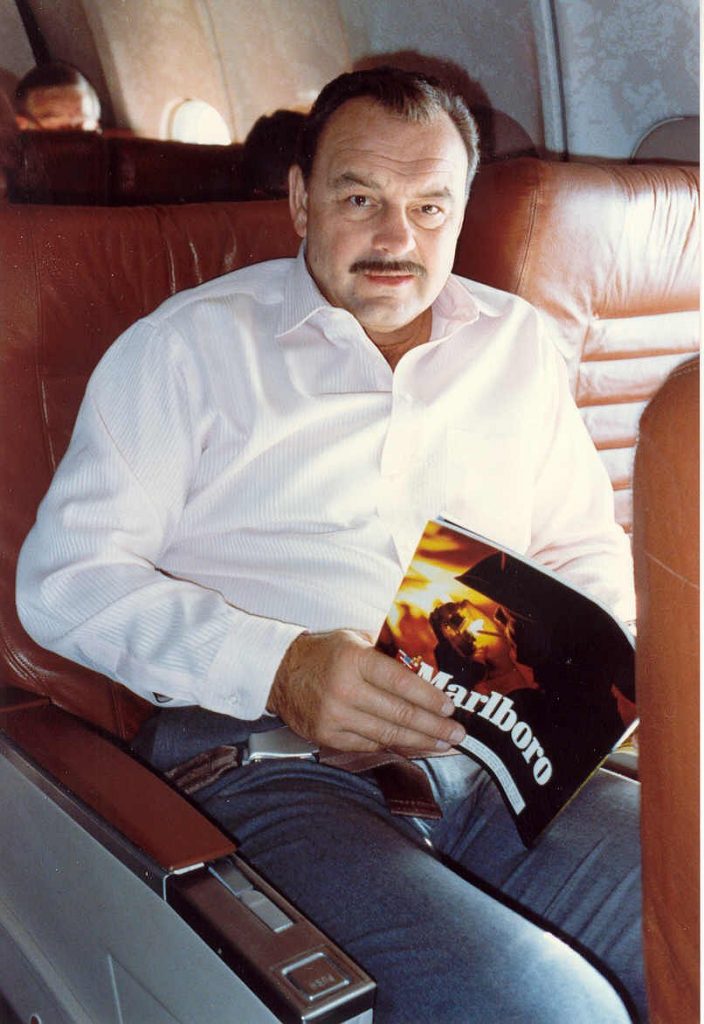

Dick Butkus was a product of his generation, an old school football player during the National Football League’s rise to prominence. He was much more than the hard-hitting middle linebacker of the Chicago Bears, as he showed us after his retirement from the NFL, when he worked as an actor and pitchman in Hollywood.

Larger than life only scratches the surface.

Butkus died on Thursday morning, in his sleep at his home in Malibu, California, according to family and Bears officials. He was 80 years old. And he was my childhood hero.

DICK BUTKUS’ IMPACT ON PRO FOOTBALL.

BY STAR PLAYERS GALE SAYERS (LEFT) AND DICK BUTKUS.

My family lived in Houston and metro Washington, D.C., during Butkus’ time in professional football, which was in perpetual change because of A) its popularity; B) its availability via television; C) competition from a rival league with more flair and personality, the American Football League of the 1960s; and D) its violence.

In 1968, at the height of his career, the Bears finished at .500, with a 7-7 record, which was actually one of the high points of Butkus’ amazing, nine-year NFL career. There were 14 teams in the NFL, and 10 more in the upstart AFL, and the late Pete Rozelle, an NFL commissioner who ruled the game with an iron fist, understood that the key to pro football’s burgeoning popularity was television.

Butkus was the third player chosen in the 1965 NFL Draft, a center and middle linebacker from the University of Illinois, 130 miles or so from his childhood home on the South Side of Chicago.

He was a hometown hero, of course, the youngest of eight children, and the first of the Butkus kids who was actually born in a hospital. His father was an immigrant from Lithuania, a man who spoke broken English and worked as an electrician. His mother toiled in a neighborhood laundry, and Butkus became a star athlete at Chicago Vocational High School, which as you probably expect was geared more toward blue-collar pursuits than a traditional public schools education.

Butkus had a way of knocking down barriers, as well as ball carriers.

JOINED THE CHICAGO BEARS IN 1964.

KNOWN FOR HIS INTENSITY.

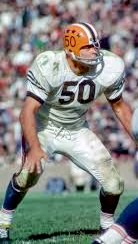

He enrolled at the University of Illinois, where he became a star as soon as he became eligible to play, in his sophomore year. (Yes, kids, freshmen had to wait their turn.) He was a 6-foot-3, 250-pound middle linebacker, calling the defensive signals, and a center, the man who snapped the ball on each and every offensive play.

He played for the last Illinois team to win a Rose Bowl, on New Year’s Day, 1964, just a few weeks before the Bears made Butkus and the late, great Gale Sayers, the Kansas Comet, the third and fourth players chosen in the NFL Draft. Sayers and Butkus were forever linked, by careers cut short by injuries, and greatness despite the Bears being one of the worst teams in the league.

Butkus and Sayers never played in a single playoff game. It was a limited postseason field, in those days, and their time with the Bears coincided with Vince Lombardi’s masterful run with the Green Bay Packers. The Bears and Packers were in the same division, of course, representing two entirely different Midwestern cities, and their rivalry was fierce even though it was largely one-sided.

IN A POSTSEASON GAME.

DICK BUTKUS, MIKE SINGLETARY AND BRIAN URLACHER.

Joe Namath and the New York Jets, a 17.5-point underdog, upset Don Shula’s Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III, 16-7, when pro football became the ultimate TV sport. “Monday Night Football” came along in 1970, about 20 months after Namath and the Jets stunned the Colts in Miami, and individual stars were everywhere.

Bart Starr, Paul Hornung and Dave Robinson in Green Bay. “Dandy Don” Meredith, Bob Hayes and Bob Lilly in Dallas. Merlin Olsen and Deacon Jones with the Los Angeles Rams. Hall of Fame quarterbacks such as Washington’s Sonny Jurgensen, the New York Giants’ Y.A. Tittle and before long, Terry Bradshaw, Roger Staubach, Kenny Stabler and the rest of them.

Dick Butkus brought out the best in them. He was an individual star on an average-at-best team. He played sideline to sideline, before such a concept was really appreciated, and his intimidating presence made for a mythical legacy in Chicago.

He embraced the violence, but he was a great teammate. He didn’t fraternize with opponents. He understood his mental strength was probably his greatest asset, because injuries quickly startes taking a toll on his career. He still was a five-time, first-team All-Pro selection, and twice was named the NFL’s Defensive Player of the Year.

DID SEVERAL MILLER LITE COMMERCIALS.

THE COLLEGE FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME, TOO.

He did more than just shed blockers and obliterate ball carriers in the hole, however. He had great hands. He had unbelievable ball skills, finishing his NFL career with 22 interceptions and 27 fumble recoveries. Once, in a game against the Philadelphia Eagles, a bad snap from center on a fourth-quarter PAT attempt skidded around the concrete-like artificial turf of Chicago’s Soldier Field.

Bears quarterback Bobby Douglass, however, picked up the ball near the Chicago 25-yard line and unleashed a desperation pass toward the end zone.

That’s where Dick Butkus was waiting. He made the catch, and showed Eagles safety Bill Bradley the ball in the end zone. Bradley swatted it away, but the Bears would win the game.

The same thing happened against the Washington Redskins, on November 14, 1971, when Douglass threw it up for grabs on a PAT attempt gone awry. Butkus made a circus catch in the end zone, in the fourth quarter after the game’s only touchdown, and the Bears escaped with a 16-15 victory over my hometown team.

I remember watching that play in the Mashek family den in Potomac, Maryland, like it was yesterday.

He was a colorful player, and his reputation was deserved. Some of his opponents said he was a dirty player. Butkus didn’t deny it.

“I never go out and hurt anyone deliberately,” Butkus once told the Chicago Tribune, “unless it was, you know, important, like a league game or something.”

I was playing high school football during Dick Butkus’ final years in the NFL, and I revered the man. It didn’t matter that he played in Chicago. I was a linebacker, too, a slow inside linebacker in the Churchill Bulldogs’ standard 5-2 “Oklahoma” defense. Always on the strong side, where the bulk of the running plays were usually going.

Good thing, because you could time me in the 40-yard dash on a sun dial.

The game was a lot more simple in those days. Just about everybody wanted to “establish the run.” Even if you COULDN’T “establish the run,” you’d pretty much die tryin’. You’d emphasize forcing mistakes, controlling the ball, winning the game with minimal risks on your own part.

Old school.

DURING HIS ALL-AMERICA CAREER

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS …

FOR MY SENIOR YEAR OF HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL.

Butkus’ injured right knee limited him to nine games in his final NFL season, 1973, which was my senior year with the Churchill Bulldogs. I walked on with the Western Kentucky football team in 1974, after graduating from high school, but I started having trouble with authority figures, something that would repeat itself over the next four decades or so.

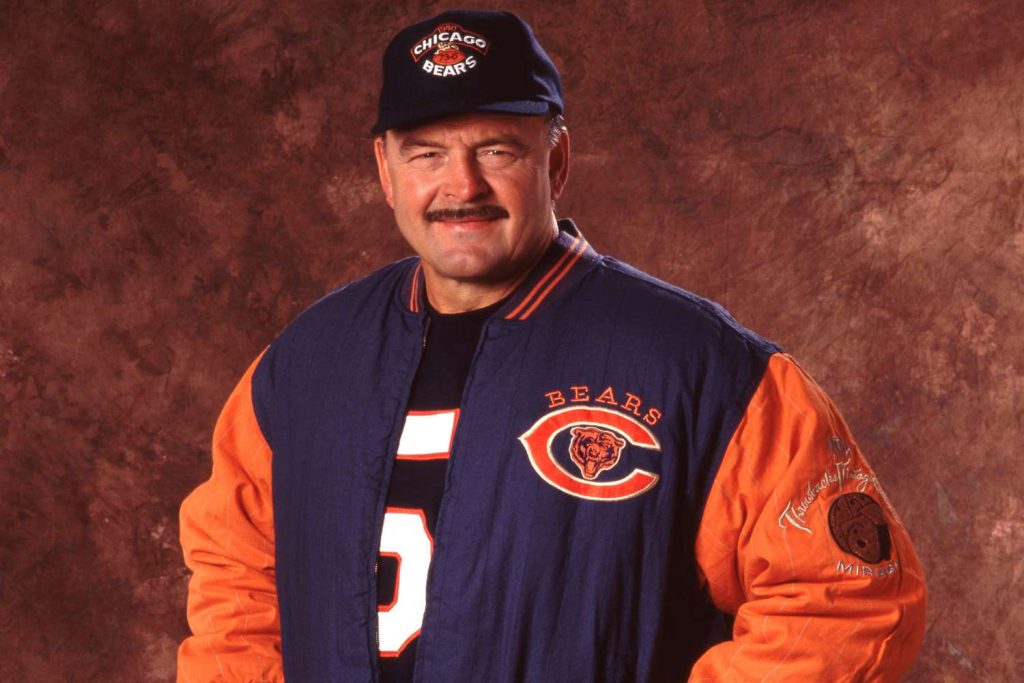

In 1985, I began my third newspaper job with the Morning Advocate in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I became the LSU baseball writer in the spring, and the New Orleans Saints beat writer in the fall. The Saints moved their training camp to La Crosse, Wisconsin, after their breakthrough 1987 season, the first winning campaign in club history, and sure enough, a year or two later, the Saints would practice against the Chicago Bears at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse campus.

That’s when Butkus’ former Bears teammate, Mike Ditka, was making a name for himself in Chicago. (The ’85 Bears won the Super Bowl in dominant fashion.)

I was in my early 30s by then, but I was still a little nervous when I introduced myself to Mr. Butkus on that warm summer day in Wisconsin. I told him that I wanted to be just like him, and I wore his No. 50 — his number at the University of Illinois — in my senior year at Churchill, because his familiar No. 51 with the Bears wasn’t available that year.

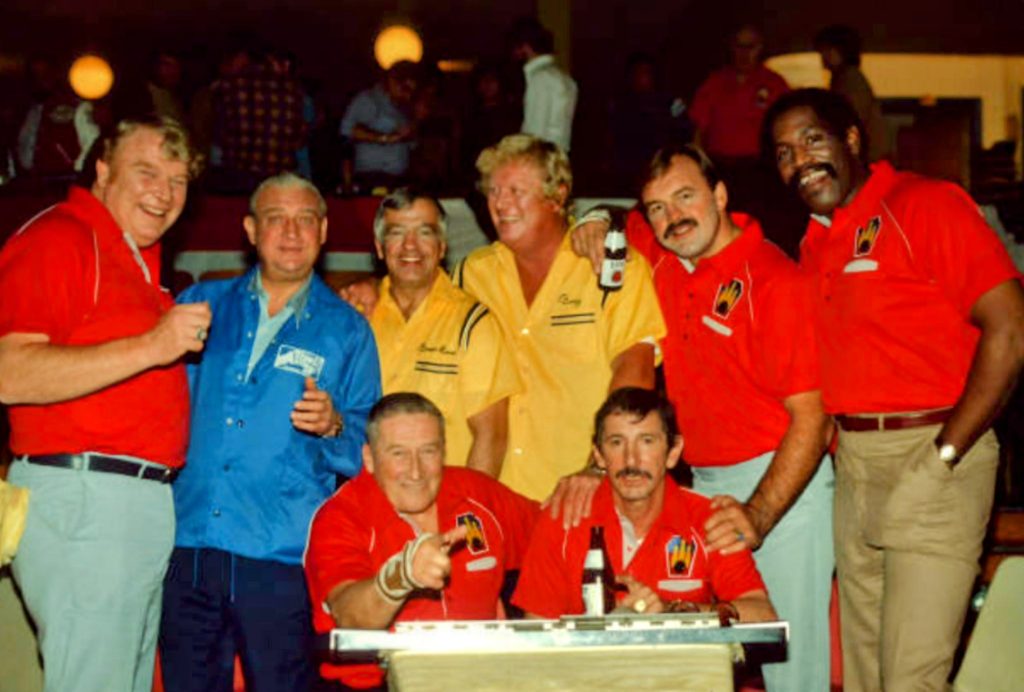

I’d seen his funny Miller Lite commercials with Bubba Smith, Ben Davidson and Rodney Dangerfield, and he went on to a fine career in Hollywood in his golden years. Watching him get around, on a cane, was a little difficult, but he seemed to do it with a smile on his face.

And he could NOT have been more gracious, more engaging. I ran into him once again at a Super Bowl function, in New Orleans, after that. But that first conversation, during the dog days of NFL training camps, always stood out in my mind.

He seemed like a great guy.

Dick Butkus was one of the greatest football players who ever lived. It’s more than a little ironic that his death was preceded by the passing of the late, great Jim Brown in May. Two of my childhood heroes, gone but certainly not forgotten.

Thanks, Mr. Butkus. For everything. You will be missed.

IN HOLLYWOOD AFTER HIS PLAYING DAYS …

“ALL WE NEED IS ONE MORE PIN, RODNEY …”