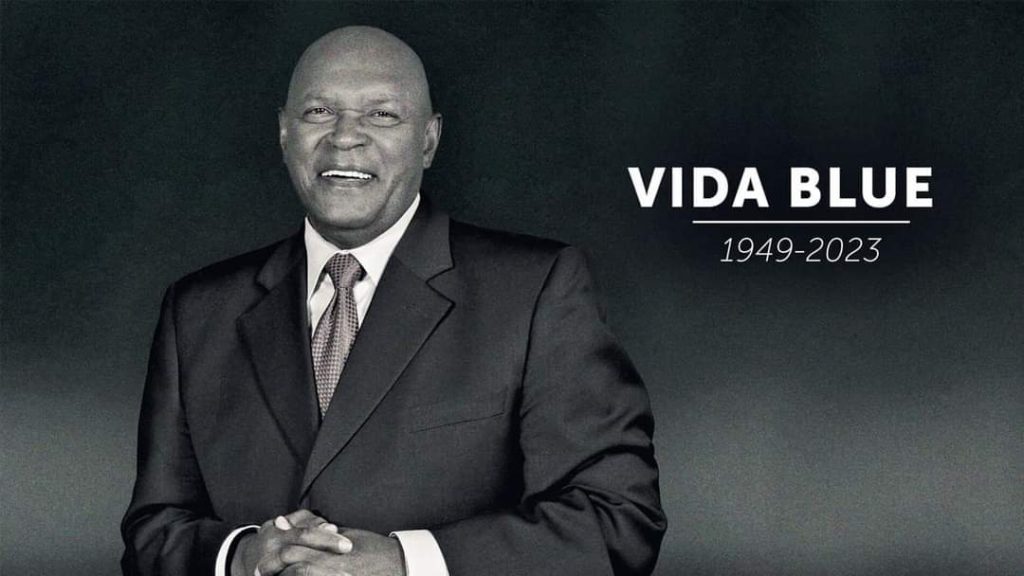

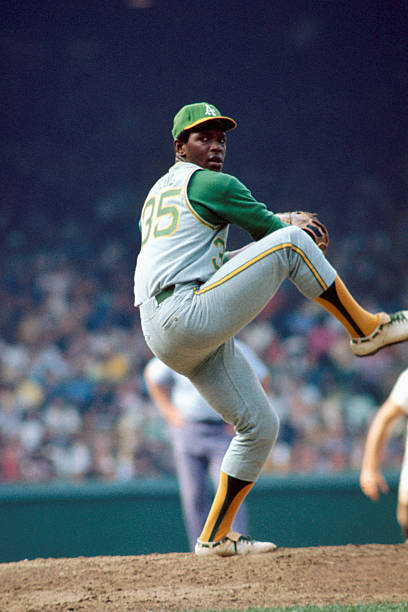

HARD-THROWING LEFT-HANDER, 73, WAS CRITICAL PART OF A’s 1970s DOMINANCE

It was the summer of 1971.

My introduction to Vida Blue, the gifted baseball pitcher of the Oakland Athletics. A cornerstone to three consecutive World Series championships. An outstanding player, over a 17-year-career, in Major League Baseball. Mr. Blue died on Saturday, at the age of 73.

Anyway, back to the surrealistic ’70s …

My family had relocated from Houston to metro Washington, D.C., one year earlier, and the following spring, there were open tryouts for two or three vacant spots for a top-flight youth baseball team known in Montgomery County, Maryland, as the Rockets.

I was a catcher who hit running backs a lot better than I hit curveballs. But I basically grew up in a baseball family — all three of my younger brothers, David, Tom, and Bill, were dedicated, dutiful baseball players — and our Dad, the late John Mashek, excelled in both football and baseball as an adolescent, first at the high school level in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Fargo, North Dakota, and then for a couple academic years at North Dakota State University.

Baseball brought my family together. Kept it together.

When we lived in Houston, Dad’s closest friend, Bill Giles, was an up-and-coming executive with the Astros, and the Giles family had three sons, almost identical in age to my younger brothers. Dad took us to a LOT of Astros games, and only later did I figure out why Mom seldom joined us on the journey to the Astrodome, and back, except for an occasional Sunday afternoon game.

Mom needed a BREAK.

A BASEBALL PHENOM IN THE ’70s.

Anyway, after making the move to Maryland, baseball was a big part of our lives, in the Mashek family. I joined the Rockets baseball team, a squad that played a couple times a week against other top-flight youth baseball teams in Montgomery County, and we were a mischievous bunch, tight on the field, and in the dugout, and a little adventurous …

Maybe, in retrospect, too curious for our own good.

They were childhood friends, Gregg Novotny, the Hahn twins — Terry and Gerry — Ted Woolschlager, a handful of others whose names elude me at the moment. Anyway, we were just about to enroll in high school — ninth grade was in Maryland junior high schools back in those days — so we probably figured we could take care of ourselves in the big city, if the opportunity would ever arise.

One hot summer day, at RFK Memorial Stadium, we got our chance.

One of the guys’ Dads agreed to drive five or six of us into the city, and drop us off, in the family station wagon, before the Washington Senators’ home game against the Oakland Athletics. Pick us up at a designated spot immediately afterward, outside the stadium.

We all paid $1.00, if memory serves, to get a ticket for the bleachers. It was a festive environment, in those days, even though the Senators would be leaving for Dallas-Fort Worth within a couple years.

The opponent?

The Oakland Athletics.

The opponent’s pitcher?

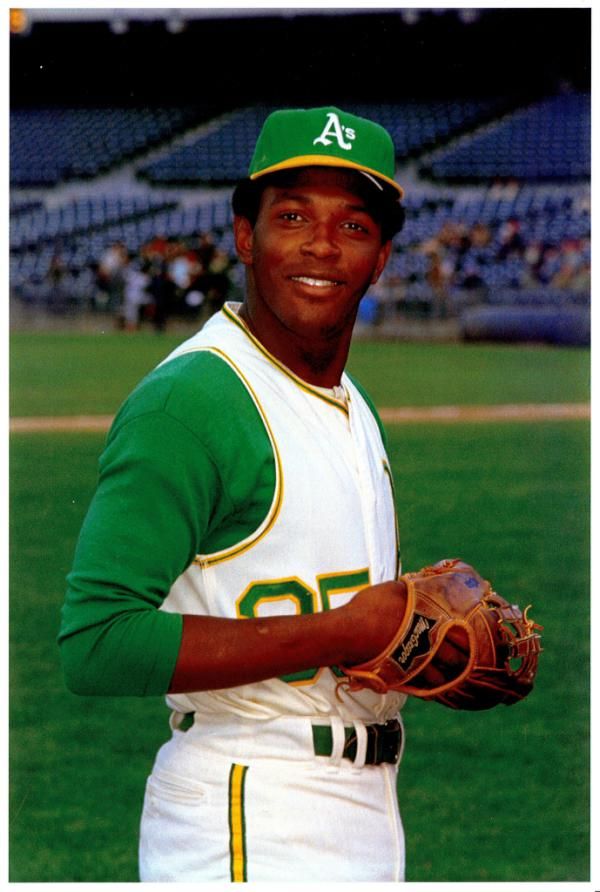

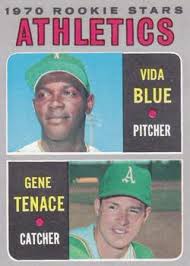

A 19- or 20-year-old phenom, a left-hander from Louisiana named Vida Blue.

We were 14- and 15-year-old brats, frankly, eager to spend a few hours away from parental supervision, anxious to see a baseball game in the RFK Stadium bleachers.

I think it was Gregg Novotny’s father, Bob Novotny, who let us pile into his station wagon before traversing downtown for our big afternoon out on the town.

I’m guessing Mr. Novotny might have arrived a little late to pick us up.

HIS OPPONENTS WITH HIS FASTBALL.

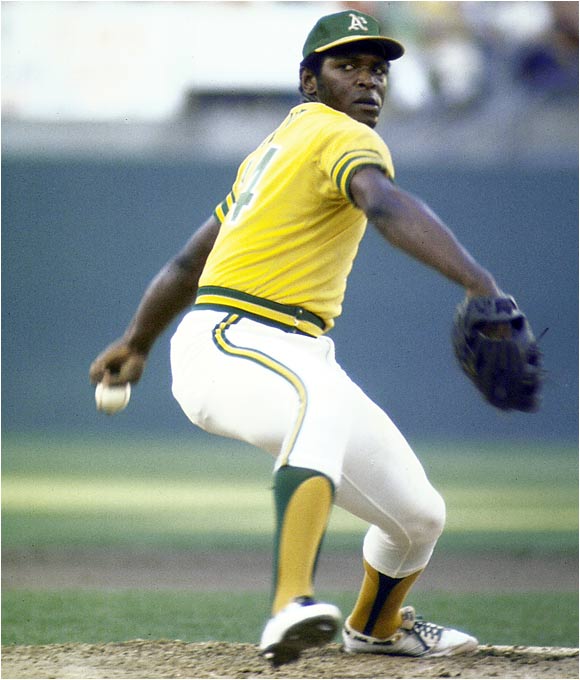

That’s because nobody, and I mean, nobody, could pick a game up like Vida Blue.

The Louisiana left-hander worked fast, on the mound. He threw the ball fast, from the mound. He kept things pretty simple.

Challenge the hitter, don’t mess around, trust your pitching repertoire.

That’s exactly what Mr. Blue did that hot summer day in D.C., when me and Gregg Novotny and Howie Stein and Fred Shulman sat in the outfield bleachers at RFK Stadium. Blue fired a 1-hitter, to tame the Senators that day, and 15 or 16 months later, the Oakland Athletics would be MLB champions for the first of three consecutive seasons.

Three straight World Series championships.

Blue had a lot to do with that, but he was part of one of the greatest teams in baseball history.

WAS A CRITICAL PART

OF THE OAKLAND A’s DYNASTY.

There was Reggie Jackson, long before his “Mr. October” days, when he was arguably the best all-around player in the game.

There was right-hander Jim “Catfish” Hunter, a colorful cat who became a trend setter in the early days of MLB free agency.

There was slick-fielding shortstop Bert Campaneris, and slugger Sal Bando, at third base. Steady catcher Joe Rudi. The stylish Rollie Fingers, a right-handed relief pitcher with a flamboyant handlebar moustache.

That was the thing about the Athletics.

They were outsiders, in Major League Baseball. My favorite team, the New York Yankees, had a club policy forbidding facial hair.

That’s how they rolled in Cincinnati, too, even before the disgraceful Marge Schott got her hands on the Reds’ tradition-rich franchise.

America was changing, in those days, to be sure.

TO THE OAKLAND ATHLETICS’ DYNASTY?

CHARLIE FINLEY HAPPENED …

Athletics owner Charlie Finley let his team express themselves, through the media, in the community. But he was a miser, a notorious tightwad. He had a collection of talent seldom seen in professional sports.

And, again, in those days, baseball was still the most popular sport in America.

The NFL was on the rise, to be sure, but college football was more of a regional draw. Boxing, with the late, great Muhammad Ali and a litany of worthy challengers, still commanded the headlines.

But baseball was pretty much still on top.

And, so too was Vida Blue.

Blue attended high school in the dark days of segregation, in Louisiana and throughout the South.

He was an accomplished left-handed quarterback, at DeSoto High School in Mansfield, Louisiana. He was recruited by major college football programs, including my hometown college, the University of Houston. But he was the Kansas City Athletics’ second-round draft pick in 1967, and he accepted a modest signing bonus — by today’s standards, or just about any era’s standards — to begin his career in professional baseball at the age of 18.

Blue was popular with his teammates, with the fans, with just about everyone besides Charlie Finley.

Finley threw his weight around like nobody’s business, which, truth be told, was fairly commonplace in professional sports in those days.

Vida Blue just threw the baseball.

He threw the baseball really well.

Mr. Blue spent nine years with the Athletics, another four years with the nearby San Francisco Giants, before closing his career with a couple two-year stints with the Kansas City Royals and the aforementioned Giants. He couldn’t sustain his early excellence on the mound, however, and was implicated in an extensive MLB investigation into drug use in the ’70s and early ’80s.

That probe has complicated his legacy, to be sure.

AMERICAN LEAGUE MVP IN 1971.

Vida Blue was a six-time All-Star. He was a star on those three World Series championship teams, and the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1971, the year me and my high school buddies got to see him pitch at RFK.

Vida went 24-8 that year, with an ERA of 1.82. He led the American League in complete games (24) and shutouts (EIGHT).

Yes, EIGHT.

True, it was a lower scoring game, in those days.

Which made Vida Blue all the more valuable.

Mr. Blue compiled an impressive pitching record, with 209 wins and 161 losses. His career ERA was 3.75. He recorded more than 2,000 strikeouts.

Baseball isn’t the TV sport that football was, and is, and it doesn’t have the constant motion of basketball, the second most popular pro sport after the NFL.

What it does have, however, is individual excellence. History. A critical part of Americana.

Vida Blue epitomized that excellence, even if his career fishtailed a bit after such an amazing start.

Rest easy, Mr. Blue. You will be missed.