SECOND ‘DOME PATROL’ LINEBACKER IS HEADED TO THE PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME

Thirty-five years ago, barely two decades into the New Orleans Saints’ history as an NFL franchise, the team held its training camp in Hammond, Louisiana.

It was the home of Southeastern Louisiana University football, although the school had dropped its football program the previous year. Small town. Frankly, pretty small time. I’m happy to report Southeastern brought its football program back in 2002, and the Lions have had their share of success as an NCAA Division 1 FCS program.

In 1986, though, the Saints were an NFL team that had yet to experience a winning season. Horrendous ownership put the team on a path to disaster in the early years, and the Saints had already had nine head coaches, interim coaches included, in their first 20 years on the field.

Saints owner Tom Benson hired Jim Finks, the architect of the famed Chicago Bears’ “Super Bowl Shuffle” team in 1985, to become the team’s general manager. The team then chose Jim Mora, a Dick Vermeil protege who had won two USFL championships with the Philadelphia/Baltimore Stars, to become the Saints’ 10th head coach.

Mora was an ex-Marine, a demanding coach, a guy who’d primarily coached on defense until he got his first head coaching job in the USFL. He inherited a roster from Bum Phillips that left a lot to be desired. There were holes everywhere, and it was Mora’s job to patch them up, and find a way to break away from the Saints’ wretched past.

One of his first moves was to sign Sam Mills, the star linebacker from his USFL Stars who was actually passed over in the league’s USFL dispersion draft.

The Saints had used their first pick on Jacksonville Bulls linebacker Vaughan Johnson, a prototypical defender who played his college football at North Carolina State. In the second round, they grabbed wide receiver/kick returner Mel Gray, who quickly became an impact player in New Orleans.

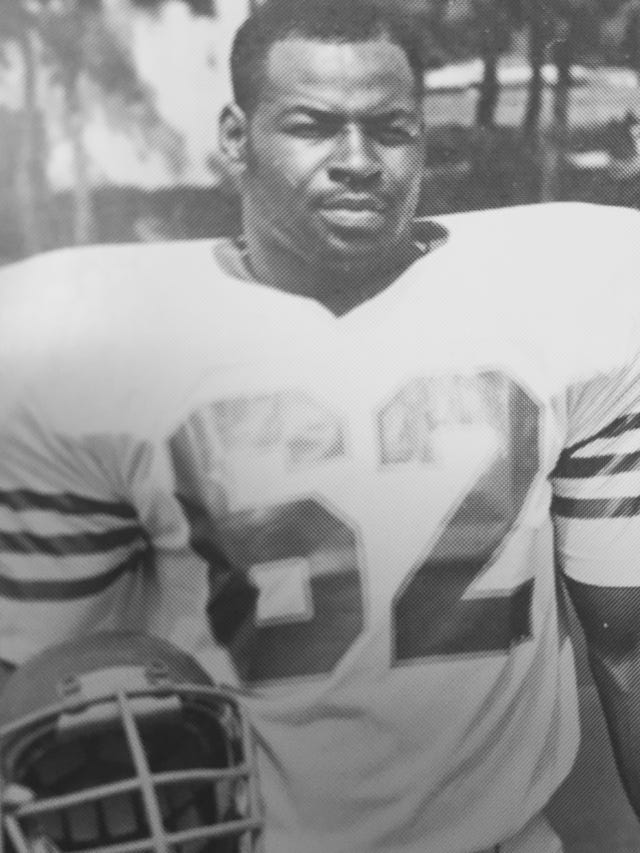

But Mora was well versed on talent available from the defunct United States Football League, and he brought Mills into the fold, telling anyone who would listen that the Saints had a keeper in the 5-foot-9, 230-pound linebacker.

I was in my second year of covering the Saints for the morning newspaper in Baton Rouge, and I had my doubts about a linebacker of that size making an impact in the NFL. Shoot, he’d played his college ball at Montclair State University, an NCAA Division III team located in Neptune, New Jersey, and while I had a vague recollection of his exploits in the USFL, I was more than skeptical about his chances with the Saints.

Then we walked out onto the practice field, for the first of many physically demanding practices that usually went well over two hours, twice a day, for six days each week.

And we saw Sam Mills for ourselves. In his element. In the suffocating Louisiana heat, in July. Perhaps I should say we “heard” Sam Mills for the first time, because when he hit somebody, on the practice field, it was usually squared up, and LOUD. After two or three days, we could see why Mora was sure that Mills could help the Saints win some games.

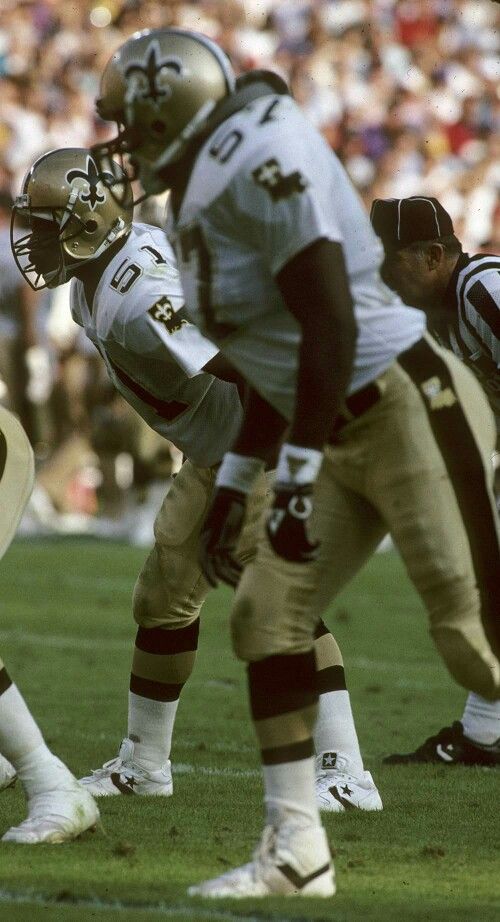

Mills was a masterful technician, a student of the game. He quickly became a starting inside linebacker with the Saints, along with Vaughan Johnson. Mora and Steve Sidwell, his defensive coordinator, were installing an aggressive, gap-control 3-4 defense, and it quickly became clear that Sam Mills was a diamond in the USFL rough. The Saints already had Pro Bowl outside linebacker Rickey Jackson, a guy who always seemed to have something to prove.

But until Mills and Vaughan Johnson came along, Jackson could only do so much.

That all changed over four months in 1986, when the Saints went 7-9, and especially the following season, when the NFL Players Association went on strike two games into the campaign.

The Saints finally had an identity.

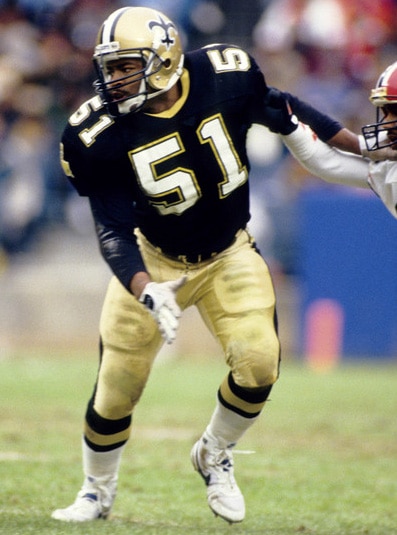

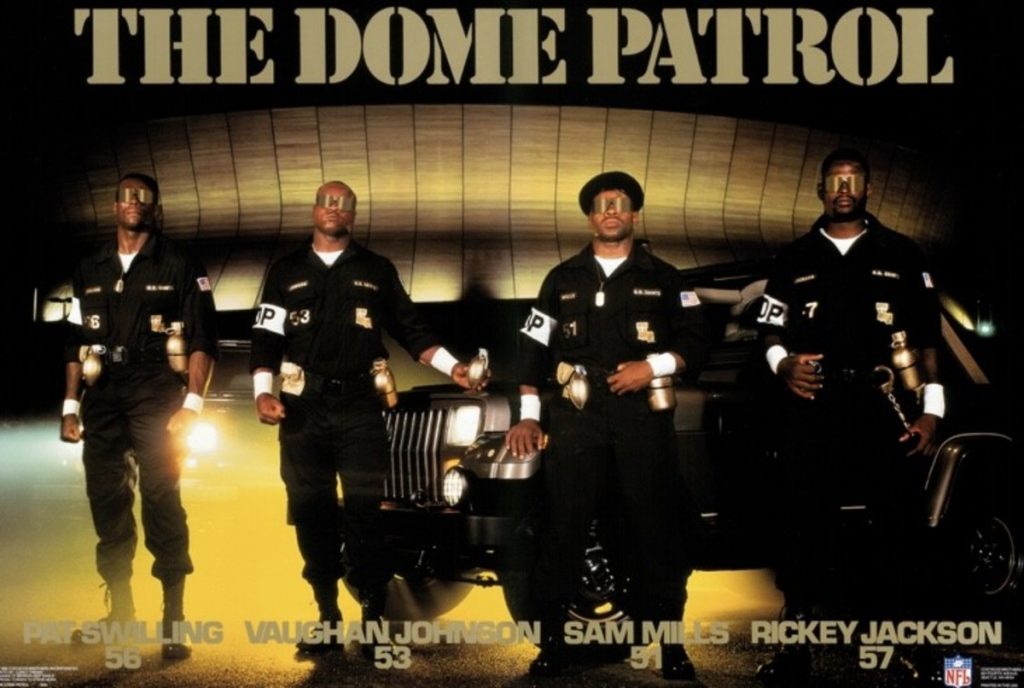

The “Dome Patrol” was born, when Pat Swilling, a third-round draft pick from Georgia Tech, became a starter at outside linebacker, opposite Rickey Jackson, while Mills and Vaughan Johnson patrolled things inside. Johnson and Mills were both sideline-to-sideline defenders, and they both packed a big wallop at the point of attack.

Watching Mills on the practice field, however, you could see a success story in the making. He was known as “The Field Mouse,” because of his size, and his tenacity. And the nickname fit.

The Saints made their first playoff appearance in 1987, going 13-2 in regular-season play before bombing in the NFC wild-card game, a 44-10 loss to the Minnesota Vikings in the Louisiana Superdome. They were still a team with some limitations, particularly on offense. And while the Saints had some proven players on the defensive line, their secondary always seemed to be a work in progress.

But Mora and Sidwell molded them into a splendid NFL defense, and Mills was front and center in that metamorphosis.

At 5-foot-9, and a chiseled 230 pounds, he played low to the ground and usually got leverage on his taller opponent. He watched game film all the time, at the Saints’ training facility in Metairie, and was known for recognizing opponents’ plays just by their formation and the quarterback’s body language.

“The Dome Patrol” Saints became a compelling story.

Mills more or less became the face of the franchise, certainly of the defense, along with his “Dome Patrol” teammates, Jackson, Johnson and Swilling.

But they didn’t get back to the playoffs until the 1990 NFL season, at which point I left Baton Rouge for a job in New York. In 1991, and ’92, the Saints won NFC West titles, but again they bombed in the playoffs, first against a division rival, the Atlanta Falcons, before falling to Randall Cunningham and the Philadephia Eagles, squandering a double-digit lead in the second half.

The Saints wouldn’t win a playoff game for another decade, but the “Dome Patrol” made them an intriguing squad.

In 1992, the entire quartet was voted NFC Pro Bowl starters.

Rickey Jackson was a street-smart guy from dirt-poor Pahokee, Florida, a big hitter and an instinctive player. Pat Swilling was a gifted athlete with exceptional pass-rush skills, and he was named the NFL’s Defensive Player of the Year when he led the league with 17 sacks in 1991.

In the middle, Vaughan Johnson and Sam Mills were a dynamic duo.

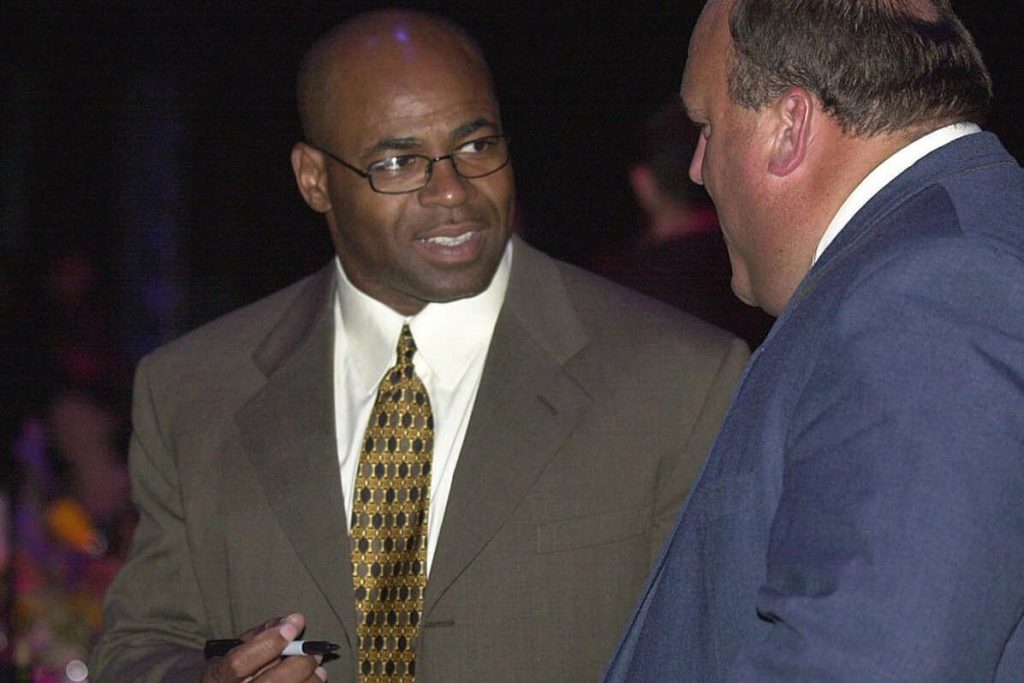

You’d always see them together, in training camp, after practice in the locker room, sometimes in social settings. Mills was a family man, with three sons, while Johnson was a freewheeling bachelor with a big laugh. Mills was kind of quiet, understated, but extremely intelligent. Polite. A great example for the Saints’ younger players.

Then, as Mora’s coaching tenure with the Saints was winding down, Mills signed a free-agent contract with the expansion -era Carolina Panthers, who had become a divisional rival for the Saints in the newly formed NFC South.

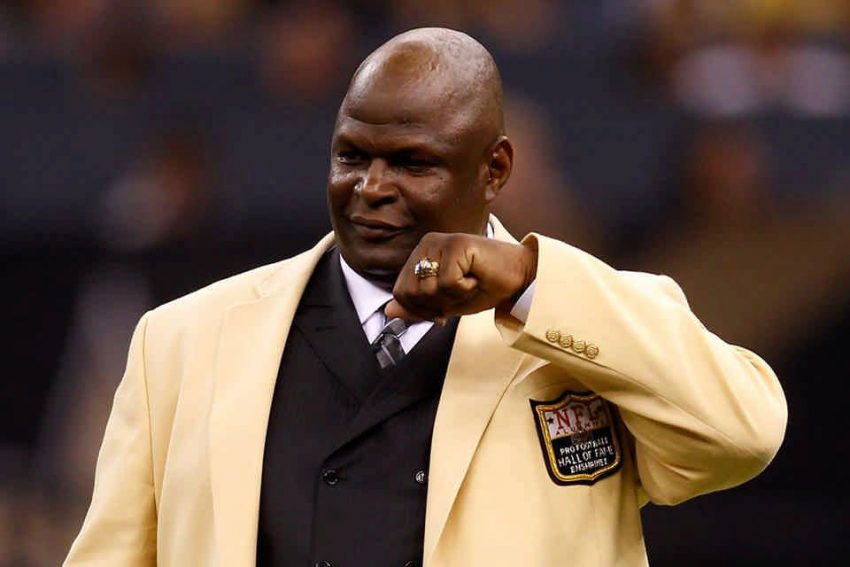

Mills continued to shine, at Carolina, and the Panthers actually reached the NFC championship game in their second year of existence. They whipped the Dallas Cowboys before losing to Brett Favre and the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field, and after one more season, Mills finally retired at the age of 38.

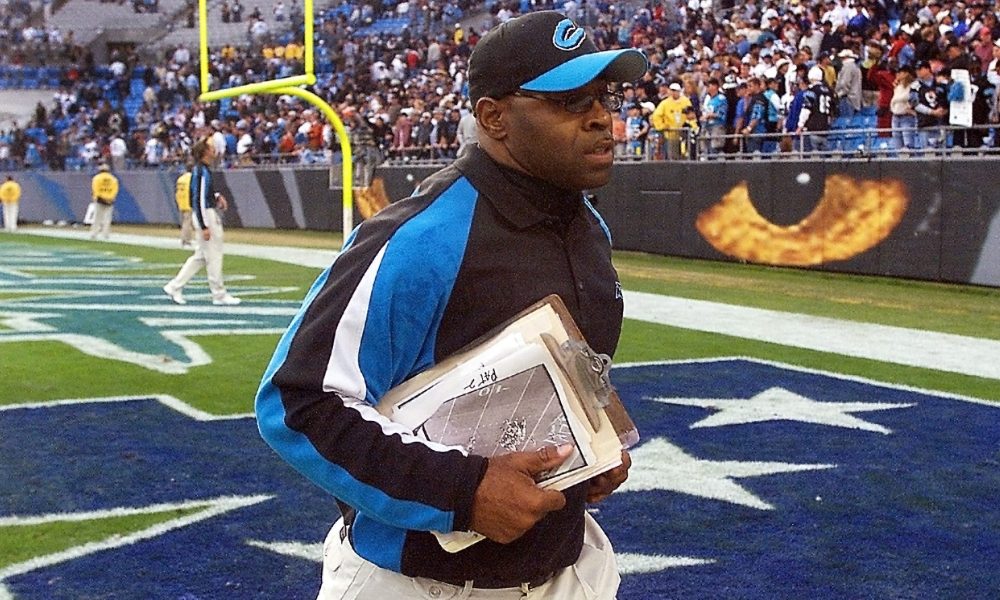

Not surprisingly, Mills became a coach after his playing days. With the Panthers.

He was diagnosed with intestinal cancer in 2003, when the Panthers went back to the Super Bowl, only to lose to Tom Brady and the New England Patriots. He continued working while undergoing cancer treatments, preferring to toil in the background while others commanded the spotlight.

I remember talking to NFL reporters from North Carolina, who raved about Sam Mills’ talents and character. It seemed a little surreal, when he died at the tender age of 43, on April 8, 2005, about 4.5 months before the landfall of Hurricane Katrina on the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts.

From time to time, Sam would get a look from the 50 or so voters from the Pro Football Hall of Fame, in Canton, Ohio. He never got very far, in the process, but in February, 2010, the colorful Rickey Jackson got the call, from the Hall of Fame. Mills was honored by the Saints’ Hall of Fame, and was in the team’s Ring of Honor, inside the Superdome, but I figured that was pretty much where it stopped.

Thankfully, I was wrong.

Jeff Duncan, a longtime sports columnist with the Times-Picayune in New Orleans, made the case for Sam Mills earlier this year, which was the final year he could go into the Hall of Fame as a modern-day player. There’s a logjam of Senior candidates, and they limit each Hall of Fame class to just one Senior candidate every year, but somehow, Duncan and some allies kept Mills in the conversation, and now he’s going to Canton.

In August.

Yes, I’m going. Maybe mix in a Cincinnati Reds game or two, on the trip.

I’ve only been to the Pro Football Hall of Fame once, when I was a slow-footed linebacker at Winston Churchill High School, in Potomac, Maryland. Visited the Hall with my parents and my little brothers. Have not had the chance to get back.

I’m going this year, come hell or high water. It should be an awful lot of fun, seeing old friends and former Saints players.

It’s hard to believe Mills has been gone for almost 17 years, and yes, cancer is a bitch, but this was a man who knew how to make a good impression. First, last, and every one in between.

Congrats, Sam. You belong. Damn straight.