(Editor’s note: I wrote this column one year ago, before launching my web site. Godspeed, Mr. Aaron. You are dearly missed.)

RIP HENRY AARON, A MAN OF PRINCIPLE AND A TITAN OF THE NATIONAL PASTIME

It was 47 years ago, come April, when Henry Aaron stepped into the batter’s box at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

Aaron’s pursuit of Major League Baseball’s career home run record took an unusual hiatus after the 1973 season, and it was obvious Hammerin’ Hank was approaching the end of his baseball career.

It was a triumph of the human spirit as much an athletic accomplishment, a moment etched in time not only in baseball, but the civil rights movement and race relations.

And, sadly, as I learned about 25 years later, it was all about race, and hatred, and Mr. Aaron’s grace under pressure most of us will never know.

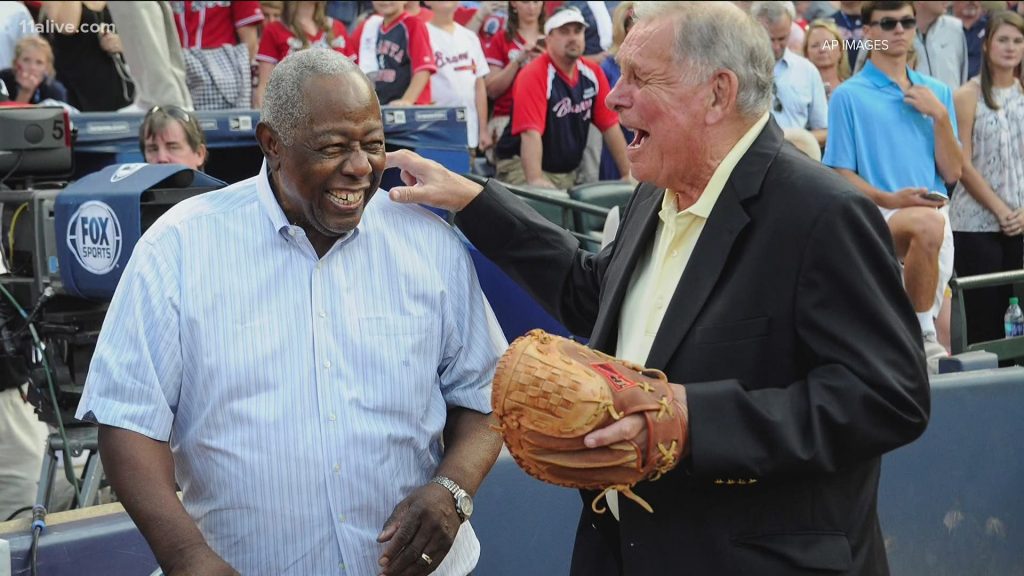

Hank Aaron died on Friday, according to the Atlanta Braves and MLB, at the age of 86. His legacy, seventy-plus years in the making, will live forever. And we’re all the better for it.

The 1974 MLB season had just begun when Aaron and the Braves faced Al Downing and the Los Angeles Dodgers at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the home of the Braves and the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons.

My father, John Mashek, was a huge baseball fan and he played both baseball and football for two years at North Dakota State before finishing his studies at the University of Minnesota.

.My dad had all sorts of baseball stories for me and my three younger brothers, Dave, Tom, and Wid. (Nickname.) Dave and Tom were primarily pitchers, and my baby brother was a power-hitting catcher with some ‘tude.

(Imagine that.)

I was 17 at the time, and I didn’t play baseball my senior year at Winston Churchill High School. I had major problems with some authority figures — imagine that — and I was two months and change away from my high school graduation.

The entire family — my late mother, Sara Mashek, made it for this one — crowded into our den on Coldstream Drive in Potomac, Maryland, for what would be a defining moment, perhaps THE defining moment, of Henry Louis Aaron’s amazing baseball career.

Even if his legacy goes a long, long way beyond the diamond.

Aaron unloaded an Al Downing pitch over the fence in left-center field and into the Braves’ bullpen for his 715th career home run, breaking perhaps baseball’s most coveted career record held by the iconic Babe Ruth. It was a celebrated moment, in most circles, but Aaron admitted he was glad it was over, after receiving hate mail for a couple years as he approached 700 home runs.

The NBC announcers let the crowd do most of the talking as Aaron began his home-run trot. By the time he got to second base, a couple hammered hams (I’m just assuming here, but c’mon …) from the University of Georgia had joined Aaron on the base paths and accompanied him to third base before he finished the feat — solo, of course — by ambling home to join his delirious teammates.

My God, it was glorious.

I knew about the hate mail Aaron had received as he was approaching Babe Ruth’s treasured record, but I had no idea about the volume of it that he received, even after the fact. It wasn’t until the late ’90s, when I was doing a multi-day series on minor league baseball, that I found out just how dark it really was.

Mobile’s Hank Aaron Stadium was only an hour’s drive or so from the Biloxi-Gulfport newspaper, where I worked for 17 years, and I was interviewing Aaron’s daughter at a Mobile Bay Bears game. I asked her about where she was when her famous father hit his 715th home run, and she glanced down for a moment and admitted she was with the FBI, in an office underneath the stands, watching it all happen.

The death threats were real.

I fumbled with my pen and legal pad as I tried to write it all down, but suddenly I was out of questions on just about everything. I was talking to Gaile Aaron, one of Henry and Barbara Aaron’s three daughters, and all I could do was apologize and thank her for her time.

Aaron received so many death threats during the 1973 season that he admitted that he was concerned he might not live to play another year of baseball. The kids from UGA who joined him on the base paths were lucky the security detail didn’t take action, just six years after Dr. Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were killed by assassin’s bullets.

It was all a little hard to process, as a teenager, and it left me more than a little forlorn when I found out some details about it while working as a sportswriter.

My late father took us to the Astrodome all the time as children, during our six years (1964-70) in Houston. Bill Giles was an Astros executive at the time and our families, with seven boys between us, became attached for a lifetime.(My brother Tom joined the Phillies organization after graduating from West Virginia University and was there, with my Dad, when the Phillies beat the Tampa Bay Rays in just five games for the 2008 World Series championship at Citizens Bank Park.)

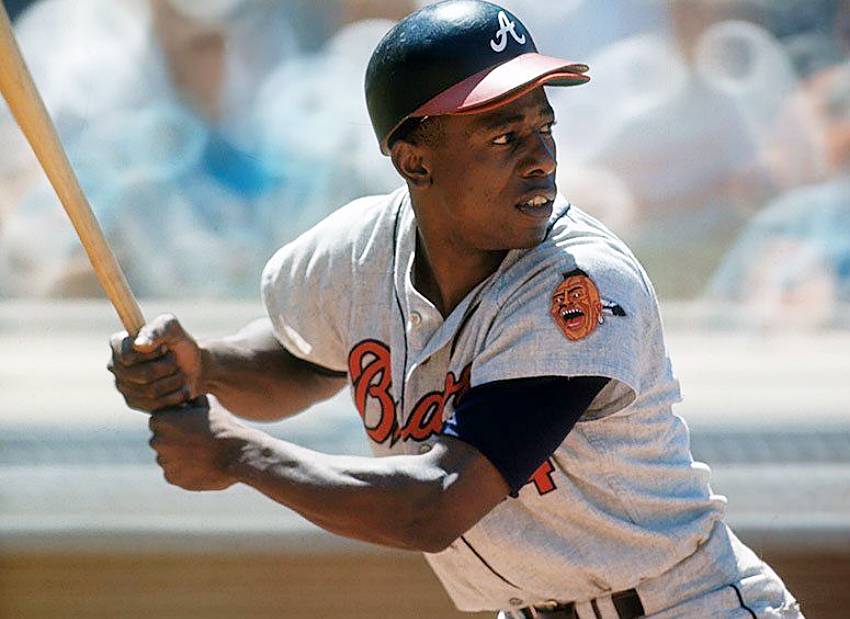

I remember Aaron’s bat speed, his follow through, his overall game, during his career with the Braves. He batted .305 with 755 home runs in his 23-year MLB career, and he never hit more than 44 home runs in a single season, but he did that THREE TIMES.

(And yes, of course, Mr. Aaron wore No. 44 during his career with the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and the Milwaukee Brewers before announcing his retirement.)

It was one thing to see Hank Aaron play on television.

It was positively another to see him play in person.

He was a five-tool guy, like his contemporaries, Willie Mays and the late, great Roberto Clemente.

Aaron could hit, for average and power. He was a great baserunner, and an underrated outfielder, with three Golden Glove awards. He won a World Series in 1957 with the Milwaukee Braves, and he worked in baseball long after his retirement as a player.

It’s a sad day, but it’s a life that should be celebrated. Rest in peace, Mr. Aaron, you are already missed.