ONE OF THE GAME’S GIANTS, THE COLORFUL JOHN MADDEN DIES AT THE AGE OF 85

He’s been a part of the nation’s most popular sport for so long, we’re not even sure where to start.

John Madden, who died on Tuesday at the age of 85, was more than just a colorful character, a likeable fella who often said he “never worked a day in (his) life,” and MEANT it, a Hall of Fame coach, an innovative broadcaster and a genuine guy who loved seeing the vast, diverse United States in the Maddencruiser.

A lot more.

Madden was an everyman who became an icon. As much a part of pro football as Vince Lombardi himself. He was a fun guy, who refused to take himself too seriously, but a guy who always had time for others. He made an impression. A big impression.

And now, as we turn the calendar to 2022, we mourn the loss of an American original, a man who embraced life, his family and his game.

John Madden is no longer with us. But in a way, he always will be.

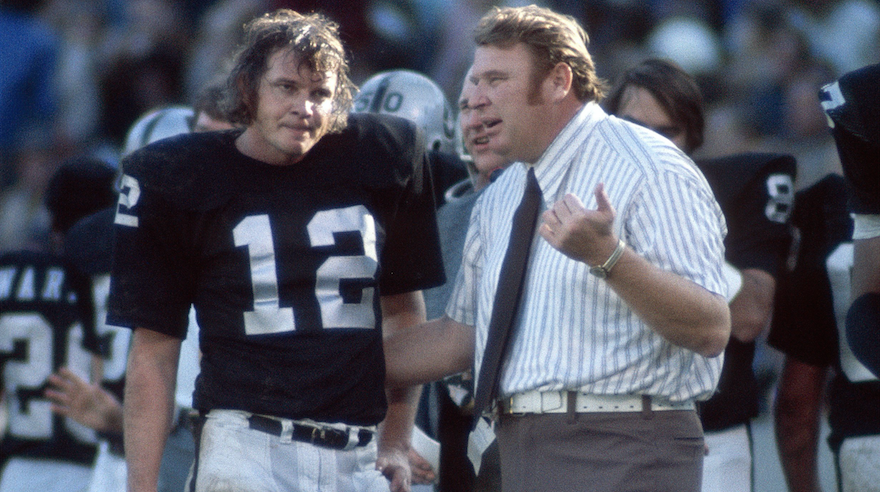

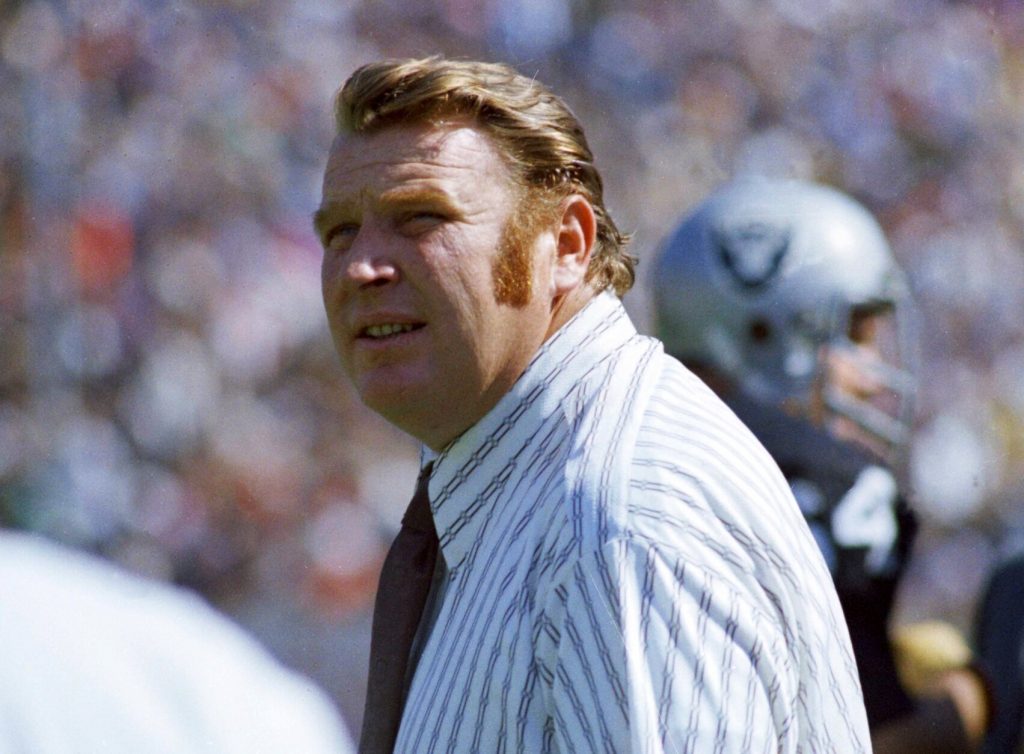

Every generation has its own vision of Madden. For the old-timers, it’s the rise of the American Football League, in the 1960s, and Madden’s powerful presence on the Oakland Raiders sideline. For the newly minted senior citizens crowd, (ahem) it’s probably his decade as the Raiders head coach, his team’s consistency, and the immediate impact he had when he stepped into the broadcast booth in 1979.

We’d never heard anything quite like it. Or him.

Madden was his own man. Take it or leave it. But he came across so forthright, so colorful, so endearing.

Generation X and its successor will remember his innovative ways as a television analyst, his quaint expressions and dime-store sound effects, and most of all his love for the game.

He did love the game. Boy, did he ever. And he made no apologies for it. (Not that he should have.)

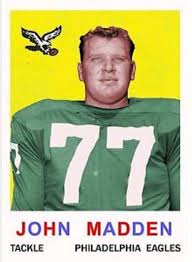

In the ’90s, he became the face of football. He wasn’t blessed with matinee idol looks, or a chiseled body. Shoot, in his playing days, big guys with a little strength and desire could find their way onto the field, provided they were willing to work. And Madden never looked at football as work.

John Madden looked at it as life.

And so we celebrate Mr. Madden’s life, just in time for New Year’s, and yes, the accolades are going to be pouring in by the hour.

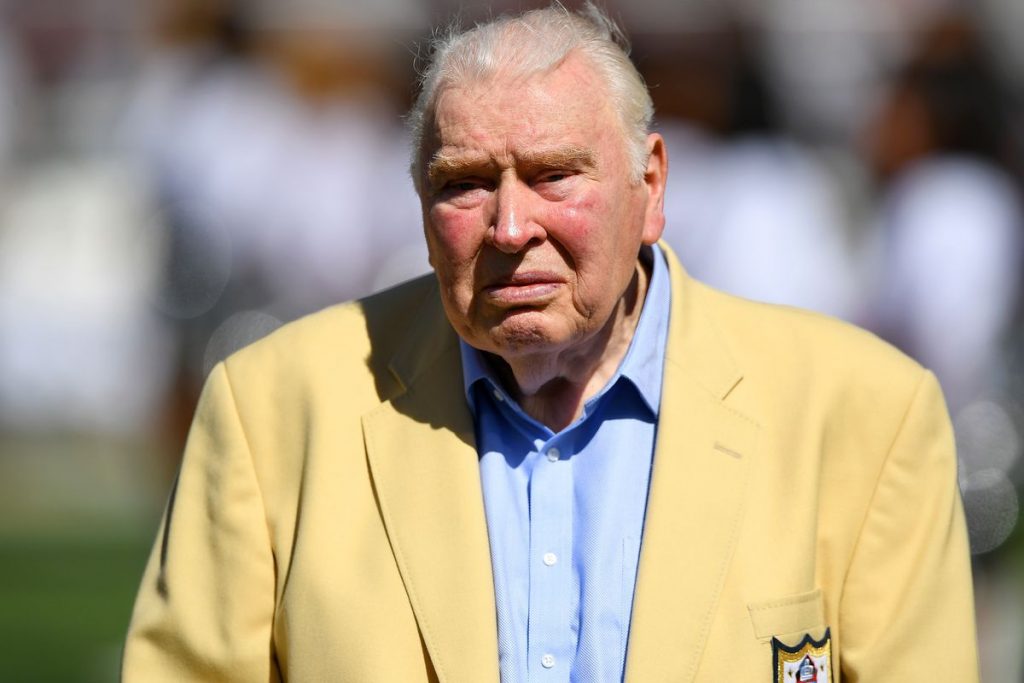

By the time Madden retired, after the 2008 season, he’d become the face of the NFL’s appeal, the centerpiece to a popular video game, an icon for the ages. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, in 2006, which was way, way too late in his life (more on that later), but it made him appreciate it even more.

If that’s possible.

Madden was football. The NFL, the AFL, big-time college football, the small school underbelly of the college game, high school football, Pop Warner football, and yes, if it counts, video game football.

(I’m not sure it does, but I’m Old School. A curmudgeon.)

Pro football is a dangerous proposition. But it’s as much a part of us as Fourth of July picnics, weekends at the beach or road trips to see the big rivalry games, when the aristocratic schools (think Alabama, Notre Dame, Texas, Ohio State and/or Michigan, maybe Ole Miss) scrap with the land-grant colleges (in no particular order, Auburn, Texas A&M, Penn State, Clemson, and in Ole Miss’ case, Mississippi State) in mid- to late November.

John Madden toiled, as a player, in the anonymous underbelly of the college game, with Cal Poly, in San Luis Obispo, California. He’d started at the University of Oregon, with his best friend, former USC and Los Angeles Rams coach John Robinson, but a knee injury forced him to take the road less traveled.

It was a journey he would get used to.

A journey he’d learned to embrace.

And nobody, at least nobody I know, thought there was anything phony about it.

I’d argue that the thing that made John Madden — well, you know, John Madden — was the chance Oakland Raiders czar Al Davis took in 1969, when he hired the 32-year-old Madden to be his head coach, succeeding John Rauch. Davis wasn’t for everybody, and he definitely marched to the beat of his own drummer.

If the enigmatic, demanding Vince Lombardi stepped out to Buddy Rich, Al Davis was Keith Moon. All over the place. If the disciplined, almost humorless Don Shula gave us John Philip Sousa, Al Davis was John Bonham. Al Davis did things his way. He made enemies as easily as he made friends. Maybe easier. But he saw something in John Madden that few of his contemporaries would envision when pro football was supplanting Major League Baseball as the nation’s most popular sport.

John Madden’s hold on professional football was enduring. Almost timeless.

And if Al Davis had gone the conventional route, if he’d hired a more mainstream coach, a taciturn taskmaster well into middle age — if not older — we might never had had a presence like Madden.

“Boom” and “doink” and Bill Parcells getting the water bucket at the end of games (victories only, of course), would have been replaced by the likes of Ara Parseghian, who insisted he didn’t see Woody Hayes slug Clemson’s Charlie Bauman after a game-clinching interception at the Gator Bowl, and Bud Wilkinson, a smooth talker who coached at Oklahoma and the NFL, but not a particularly affable fellow, or, Heaven forbid, another latter-day Mute Rockne, as if the only way to football immortality was through South Bend, Indiana.

Nope, not in Madden’s caase.

Madden posted the NFL’s best winning percentage, with a 103-32-7 record in regular-season play, and a 9-7 showing in the playoffs, over his 10 memorable seasons at the helm of the Oakland Raiders.

Madden didn’t have a lot of rules. He was nobody’s taskmaster. But he inspired loyalty. Be on time, pay attention, and “play like hell” when the time came. The Raiders weren’t the team of the ’70s — that would be the Pittsburgh Steelers, of course, with their four Super Bowl victories, with two back-to-back titles (1973 and ’74 seasons, and 1978-79), but I’d argue that never would have happened without the Raiders’ presence.

And the one time the Raiders broke through, in a memorable 1976-77 season, they had to win, on the road, in Pittsburgh, to get to the Super Bowl. Anyone who thought the Minnesota Vikings had a chance in that game must have stumbled into some serious hallucinogens, or spent his or her entire life in the Twin Cities, or maybe the Mayo Clinic.

The Snake and The Stork and The Tooz and the Raiders’ head-hunting secondary — Jack Tatum, the assassin from Ohio State, “Old Man Willie” Brown, the Human Quote Machine, George Atkinson, and later on, after Madden’s retirement, the dynamic cornerback duo of Lester Hayes and Mike Haynes — sensed their time had arrived. Riverboat gambler quarterback Ken Stabler, rangy linebacker Ted “The Mad Stork” Hendricks and Bourbon Street prowling John Matuszak — you know, the inspiration of the “Cruisin’ With The Tooz” literary effort — were the NFL’s Bad Boys, but they meant business, too.

They won.

They won, colorfully.

Peter Richmond’s amazing book, “Badasses,” took you inside the Raiders’ locker room, to their freewheeling training camp, to Otis Sistrunk and “The University of Mars,” and kept you there. Just like John Madden did in the present time.

Franco Harris won four Super Bowls with Chuck Noll’s Pittsburgh Steelers, but he’s as remembered as much for the “Immaculate Reception” against Madden’s Raiders, at Three Rivers Stadium, as he is all the records and trophies and everything else. Harris and ex-Raiders linebacker Phil Villipiano have almost made the “Immaculate Reception” a cottage industry, all by themselves, with their good-natured banter while both insisting they were in the right when Harris plucked (or trapped, depending on your perspective) Terry Bradshaw’s deflected pass (if ‘richochet’ is allowed as a verb here, it would be more appropriate) off the damp carpet in the final seconds at Pittsburgh on December 23, 1972.

NFL Films caught John Madden pleading with the officials, who were reluctant to make a ruling on the play, and Madden later admitted he never recovered from that defeat. Even if, if you gave him truth syrum, he probably did.

John Madden made football fun.

It’s a violent sport, it is. There have been deaths on the field. Steroids became a huge problem for Pete Rozelle and the NFL heirarchy in the ’80s. Criminal behavior, off the field, sometimes commanded the headlines. Concussions, and CTE. We could go on, and on, and …

That’s pretty much what Madden did.

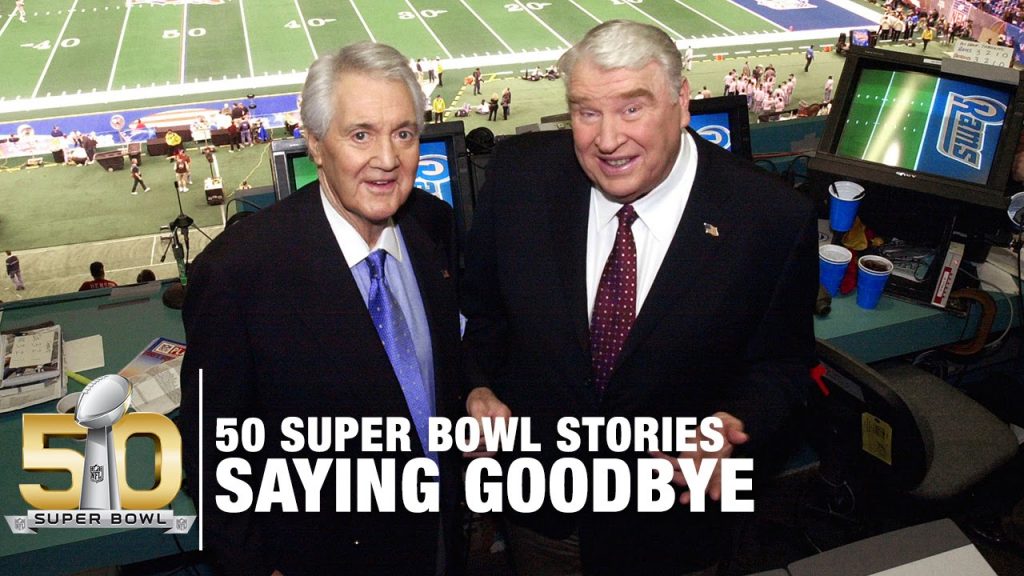

First, with the understated Pat Summerall. Then, with Al Michaels, the smooth broadcaster who asked us if we “believed in miracles” after the U.S. hockey team defeated the hated Soviets in the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. Madden made his mark in commericals, particularly with Miller Lite, after leaving the sidelines, and he became Amtrak’s most famous passenger until the Maddencruiser started taking him around the country, from one NFL destination to another.

If there’s a more politicized Hall of Fame voting process than the Pro Football Hall of Fame, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen it. (Although some would argue it’s baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.) The Hall of Fame voters weren’t sure if Madden should go in as a coach, or a contributor, like it really mattered, and he had to wait his turn, like a lot of the other inductees in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

(Full disclosure: I’ve been to both Canton, and Cooperstown, just once. Each. Cooperstown during my time on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, while on vacation, during the summer, in 2003, and Canton, with my Mom and Dad, and three younger brothers, when I was a wide-eyed high school football player and wannabe badass in suburban Potomac, Maryland, in the early ’70s.)

But I try to watch the induction ceremony every year, and I was lucky enough to cover a handful of Selection Saturdays, during Super Bowl week, in my sports journalism career. Rickey Jackson’s selection to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in February, 2010, was almost a sign that the New Orleans Saints would win, the next day, for the only time in franchise history, just 4.5 years after Hurricane Katrina laid waste to New Orleans and much of the Gulf South.

I remember what Madden had to say, when he was enshrined, that he figured the busts, inside the museum, “talked to each other” after the lights went out and the Hall of Fame personnel went home, at night. Especially, I’m guessing, the deceased. Vince Lombardi and George Halas snarling at one another. Tom Landry and Tex Schramm giving their peers the high-and-mighty treatment in the middle of the night. Pete Rozelle himself scolding the likes of Joe Namath, Jim Brown, Dick Butkus …

Wait a minute. Butkus, Brown and Namath, I’m happy to report, are all still with us.

But only John Madden would think of such a dialouge, an open flirtation with the hereafter, a reason to make the pilgrimmage to Canton, to see the Pro Football Hall of Fame for all of us.

If you love pro football, chances are, you love John Madden.

You may not have even liked his broadcasting style. You might have been a fan of the Steelers or the Denver Broncos or the Kansas City Chiefs, and HATED the Raidahs, and their reputation, their extracurricular activities on the field. You’d still find a soft spot for Madden.

He brought people together.

Mr. Madden didn’t try to overwhelm you with his intellect. He loved football, he loved his family, he loved calling the game in the booth. Once, when I was toiling in Baton Rouge, covering the Saints and LSU baseball, the CBS folks brought the media in for a white-tablecloth luncheon, in a New Orleans hotel, two or three months before Joe Montana and the San Francisco 49ers slapped John Elway’s Broncos all over the Louisiana Superdome, to the tune of 55-10.

Madden took five or six of us media types onto Canal Street, where the Maddencruiser was parked, and showed us around. I’m not sure how I finagled that one, but I did. Madden put everybody at ease, before he left us in stitches by spinning a couple off-color yarns about memorable moments in the luxury bus.

With a perpetual smile on his face.

We all should be so lucky. So grateful. So humble. Yes, humble.

Madden, the everyman who became every man’s NFL broadcaster for the better part of three decades.

He’s gonna be missed. A lot.

But John Madden will never be forgotten. Not in our lifetimes. And we’re better for it.